Taken To School

One weekday morning in mid-Spring I found myself in Towson, MD walking RB, my seven-year-old granddaughter to her school bus pick-up when RB turns to me and asks, “What does Cinderella mean?” I told her that I wasn’t sure but I’ll look it up when she’s in school. Then she said that Cinderella’s real name is Ella, and that cinder means ash. I added that Ella – I never knew Cinderella’s real name was Ella – probably had to remove ashes from her stepmother’s fireplaces, and that’s how she likely got her name.

My granddaughter then said that I should read the book while she’s in school so we could discuss this later. I protested that her mom already had me scheduled to repair two lamps, watch a live stream of a medical conference, and meet with pest control folks mid-afternoon for the monthly home check-up.

“No excuse,” was what RB told me, as we turned our backs to traffic on the side of the street to play our friendly game of who-can-hear-the-school-bus-first.

“First of all,” RB said, “I asked you what does Cinderella mean. Not how Ella came to be known as Cinderella. And I have long noticed that you often give me answers to questions that sound sort of right but are wholly based on your form of casual deduction and not on empirical evidence. All I ask is less of the former and more of the latter.”

With the bus coming I didn’t think it useful to disagree with RB as we waited to hear the bus engine struggle to get up the hill at the end of the block where we waited..

“When you were in first grade, in, what was it, 1957 or so,” RB continued, “you had what we now refer to as a modern education. You memorized and deduced. Memorized and deduced. Memorized and deduced. Over and over and over and over again. The only good thing about your education was phonics, and why was that good? Because you learned how to decode letters as symbols, symbols for sounds, sounds that represented words, words that have meaning, meaning that is framed by culture, all while learning how to spell. And yes, you’re a top-notch speller, a great GREAT achievement, an achievement no more than twenty-million adults making less that $30,000 annually can claim. But your reliance on deduction is a crutch, Big Dawg.”

My granddaughter calls me Big Dawg these days. I call her Little Dawg. And sometimes she calls me Big Raccoon, and other times she calls me Surely, ever since I introduced her to Leslie Nielsen and Airplane.

I didn’t think it was the best time to bring up the big question I really wanted RB to answer, especially knowing that the bus could come at any moment, but I did anyway. RB could think about this while in school today. “So, RB,” I asked, “what then is the meaning of truth? To you?”

The kid must’ve already thought a lot about this, because her eyes widened as she began without the least bit of hesitation. “What do you want, Big Dawg? Metaphysics? The properties of sentences? How about beliefs, mystical, scientific, or farcical? Maybe tautological propositions? Or maybe bold assertions such as ones found in the New Testament, like the one found in John 14:6, where Jesus states that ‘I am the way, the truth, and the life. No one comes to the Father except through me.’”

As RB grew from infancy, I never imagined that my granddaughter would take me to school. I next expected RB to deliver the exchange between Tom Cruise and Jack Nicholson in A Few Good Men. “I want the truth!” And “you can’t handle the truth.” Instead she said, “I hear the school bus. You read Cinderella and we’ll pick up this conversation later today, OK?” I greeted the bus driver, Mr. Jimmy, who knows me from past visits, and watched my granddaughter hop up the steps on her bus.

I walked back to my daughter and son-in-law’s house. “Where did I go wrong?” I thought to myself. “And more important, where is my granddaughter headed?”

As soon as I got back inside I made myself coffee, sat down in the kitchen, and thought that before I can understand what RB knows, it would be prudent for me to sort out how I came to know what I know. I immediately recalled a traumatic and formative incident from second grade, though no one’s still around who can explain its impact on me 65+ years later. I was in second grade at PS 244 in East Flatbush, Brooklyn, and because of my then (and now legendary) seven-year-old intellectual development, I was to be promoted to third grade during the middle of the school year. I was elated. This was the outside recognition of my nascent intellectual abilities, the confirmation by a respected authority other than my parents of my bright future, and a first-rate opportunity to bid farewell to my classmates, some of whom were still forming incomplete thoughts while eating large quantities of paste. I imagined myself waving to these classmates in my rear view mirror while they begged what would become my former teacher to fill their empty paste pots.

But just before I was promoted, my parents moved from Brooklyn to Hicksville in Nassau County. I had to change schools. My mother, a teacher who knew her way around school bureaucracies, marched me into the Dutch Lane Elementary School to register me for class with a letter from my Brooklyn school that indicated I was to be placed in third grade, and not second.

To this day I remember what the Hicksville school administrator told my Mom with regard to my third grade placement.

“We don’t do that here.”

And with those five words I was crushed, placed in second grade in a school system that appeared to me, more than sixty years ago, to be doing the class work I had done in first grade in Brooklyn. I couldn’t stop thinking about how wrong this was, even though I did not yet understand that the public-school education I was getting in Brooklyn was far better than the one I’d get on Long Island.

I made peace with my situation only because I barely knew the meaning of tragedy. Nor did I yet know the meaning of an abyss – or ennui for that matter – nor was I yet sufficiently coordinated to throw both of my arms up into the air and ask, “God, why me?” I also don’t think I had a clear notion of who God was at that point in my life, and to that observation I can only say, “Some things never change.”

But enough about me and my childhood trauma. And just to show you how one trauma can be compounded like interest on a third-rate money market account, my parents moved again during the summer following my completion of second grade to Riverhead in eastern Suffolk County, to a school system which, again, to me, and more than sixty years ago, was even further behind than the school system I encountered in Hicksville. And that’s where I spent third, fourth, fifth, and sixth grades, and where I first learned about multiplication tables, serial commas, nok hockey, self-consciousness, and the evil twin of self-consciousness, self-awareness.

But back to RB, my granddaughter. In 2024. How did she accumulate these ideas she has? How did she learn to process information? How did she come to know what she knows? When I was her age, my middle brother, Len, used to say that my tongue was always hanging outside my mouth, like a dog, and that I had yet to learn how to diaper myself. RB, on the other hand is spouting higher-order concepts.

Unlike Socrates, who according to Plato argued that the unexamined life is not worth living, I’ve always felt that the overly examined life will drive you nuts. Therefore I decided to not drive myself nuts and to wait until my granddaughter returned from school to continue this journey into meaning and truth.

At around 4:00pm I met my granddaughter at the school bus drop-off point, whereupon RB handed me her book bag, water bottle, lunch box, and a copy of The Autobiography of Solomon Maimon, a great book about the experiences of a shtetl-born Orthodox Jew during the Renaissance, a real seeker who saw science and nature where others saw ritual. “This is for you to read,” she said. I didn’t think it was a good idea to mention that I had already read the book. When I was 70.

I prepared a post-school snack for RB while we discussed the vocabulary words she worked on today – delicious was one of them and one I challenged RB to spell – and we both agreed that there are many words that can be read in context without being able to spell the same words out of context. “That,” RB said, “is why reading is so important. The more you come across such words, the easier it is to visualize them and then spell them.”

“But what about conceptual reach?” I asked.

“What do you mean, exactly?” RB asked.

“I mean how does someone, you, for example, learn to see the world, its operations, its generalities, its anomalies, and learn to organize all of this stuff into useful knowledge, and how can you use this knowledge to lead a useful life?”

“Surely you jest,” RB responded while nailing a perfect Robert Hays imitation. But I knew what she meant.

“Lead a useful life? Lead a useful life? I’m taking a school bus with kindergarteners and kids in the first through third grades. We talk about lots of things, from fingernails to Taylor Swift, from Wheel of Fortune to learning to ice skate. Your ‘conceptual reach’ question is interesting,” and then she paused for what I knew to be dramatic effect, “but says more about you, your past, and your future, than it does about my present and my future.”

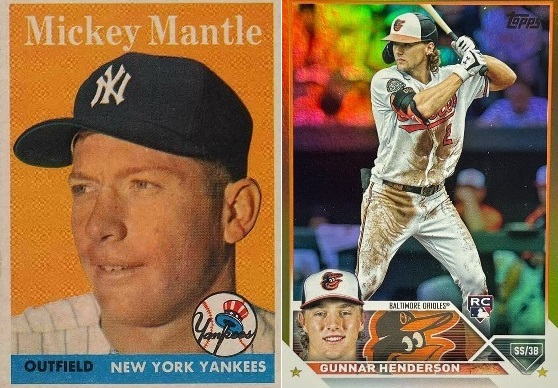

Then RB added, “Look at it this way. Your Mickey Mantle is my Gunnar Henderson.”

When we watch baseball on TV, I’ve told RB more than once that Mickey Mantle was the only real hero I ever had as a child, and by following Mantle’s career trajectory, I learned lots about math, baseball history, US history, and also learned that trajectory has a lot in common with tragedy, because no trajectory continues on its upward course forever. I told RB the story of Icarus and Daedalus to illustrate my point. Later in life I learned that the root words for tragedy and trajectory are completely different, and I was reminded then that knowledge based on faulty deduction is no different than knowledge based on belief. RB follows Gunnar Henderson of the Baltimore Orioles for reasons that only she knows right now. I suspect that one of the reasons is that RB watches Orioles games on TV, often with her Dad, like I used to listen to Yankees games on the radio. Frequently.

“Thanks, RB, I really needed that,” I said.

“And if I were to have a setback due to some bureaucratic error in second grade,” continued RB, “I now know that stuff like this happens in all grades and to all students, and if I were you, Big Dawg, I wouldn’t worry so much about what happened 65+ years ago, OK?”

“OK,” I said, “What do you want to do?”

“What do you know about Baruch Spinoza?” RB asked.

“A little,” I said, and I told her what I knew as we practiced cursive writing. RB wants to be able to write her full name in cursive. I told her that with practice, she’d be able to sign her parents’ signatures as well.

Then I explained what forgery was. RB understood immediately, of course.

Let RB know that Cinderella’s last name was Guru. Just ask Captain Beefheart who shortened her first name to Ella in order to fit the parameters of his quintessential song.

https://youtu.be/2YjTUQIfmRs?feature=shared

WOOOW! Ah, haha, ha!!!! Especially loved the description of classmates eating paste! What a great piece! Thakns for sending it my way! Write on!

Reading this, I feel a little like George Wilbur when Vinny recalls him after Mona Lisa Vito testifies that those tire marks were made by a Pontiac Tempest (leaving aside evidence that the Buick Skylark indeed was available with limited slip differential but the trademark “Posi-Traction” was not available to the Buick division, the bodies of the Tempest and Skylark were not identical, and the Corvair also was available with both limited slip differential and independent rear suspension and to the untrained eye could have been mistaken for a Tempest–although I confess my research ended before I could confirm which of those models were available in metallic mint green), and asks,

“So . . . whuddja think?”

“Very impressive.”

“And she’s cute, too.”

“Uh . . . very.”

I cannot add much to the general epistemological musings of this post, but I can affirm that half of what I know about trial work derives from that movie.

Another charmer and two stars no less. As for me, I still can’t handle the truth, but I do love the wall. Be well.